Laminitis

by Linda Veinot

Laminitis is a common, painful, and potentially disastrous condition of the horse foot that has been recognized for hundreds of years. Currently, a horse is considered to have laminitis when there is a failure of attachment between the coffin bone (distal or third phalanx or P3) and the inner aspect of the hoof wall. To understand laminitis, it is necessary to understand the structure and function of the horse foot

(Fig.1).

The Anatomy of the Foot:

There are two main areas of interest when considering laminitis. The first is how the coffin bone is attached to the hoof. The second is the blood supply to the foot.

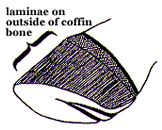

The main bone of the foot is the coffin bone, so named because of being encased inside the hoof. It gives the foot its shape and the rigidity needed to bear weight. The coffin bone is actually suspended in the hoof, attached by a Velcro-like arrangement of specialized structures called laminae to the inside of the entire length of the hoof wall. There are two kinds of laminae. Dermal laminae grow outwards from the laminar dermis attached to the coffin bone. They are made of living connective tissues that fold into primary finger-like structures; each of these in turn is folded into hundreds of feather-like secondary laminae. These dermal laminae interdigitate with corresponding epidermal laminae, each again of primary and secondary generations, that project inward from the inner horny surface of the hoof wall, anchoring the coffin bone to the hoof wall (Fig. 2). The amount of folding in the laminae increases the surface area of bonding, reducing the stress across the junction. The interface between epidermal and dermal laminae is called the basement membrane, which contains the biological "glue" that joins the two structures. The coffin bone is attached to the sole by a vascular connective tissue called periosteum. The digital extensor tendon attaches to the top of its dorsal (front) surface and the deep digital flexor tendon attaches to the top of its plantar/palmar (back) surface allowing extension or flexion of the foot respectively as the horse moves.

(Fig. 2) |

The Anatomy of the Foot: There are two main areas of interest when considering laminitis. The first is how the coffin bone is attached to the hoof. The second is the blood supply to the foot. The main bone of the foot is the coffin bone, so named because of being encased inside the hoof. It gives the foot its shape and the rigidity needed to bear weight. The coffin bone is actually suspended in the hoof, attached by a Velcro-like arrangement of specialized structures called laminae to the inside of the entire length of the hoof wall. There are two kinds of laminae. Dermal laminae grow outwards from the laminar dermis attached to the coffin bone. They are made of living connective tissues that fold into primary finger-like structures; each of these in turn is folded into hundreds of feather-like secondary laminae. These dermal laminae interdigitate with corresponding epidermal laminae, each again of primary and secondary generations, that project inward from the inner horny surface of the hoof wall, anchoring the coffin bone to the hoof wall (Fig. 2). The amount of folding in the laminae increases the surface area of bonding, reducing the stress across the junction. The interface between epidermal and dermal laminae is called the basement membrane, which contains the biological "glue" that joins the two structures. The coffin bone is attached to the sole by a vascular connective tissue called periosteum. The digital extensor tendon attaches to the top of its dorsal (front) surface and the deep digital flexor tendon attaches to the top of its plantar/palmar (back) surface allowing extension or flexion of the foot respectively as the horse moves. |

|---|---|

(Fig. 3) |

In addition to attaching the coffin bone to the hoof wall, the laminar dermal region also contains sensory nerves that inform the horse about the position of its hoof, is involved in thermoregulation, and carries the blood vessels that nourish the hoof and allow growth. The blood supply to the equine foot is unusual (Fig.3). Arteries control the amount of blood reaching any area of tissue in the body. All arteries have receptors in their walls that can bind specific chemical messengers circulating throughout the body. The binding of these chemicals causes the dilation or constriction of the arteries changing the amount of blood reaching the tissues. Blood rich in the oxygen and nutrients necessary to sustain living tissues is carried in arteries from the heart to the foot. It then passes through a capillary bed in the dermis where oxygen and nutrients can diffuse to the cells. The oxygen-depleted blood full of carbon dioxide and waste products is then carried away in veins. This is similar to the circulation in all tissues of the body. However, there are also arteriovenous shunts in the horse foot, which allow the arterial blood to go directly to the veins, bypassing the capillaries. When these shunts are open, little or no blood is going to the tissues. The shunts are thought to protect the capillaries from unduly high blood pressure. |

What is Laminitis?:

Laminitis is the failure of the attachment between the coffin bone and the inner hoof wall. With separation of the laminae at the basement membrane, the weight of the horse plus the significant forces of locomotion causes the coffin bone to drive down into the hoof capsule and possibly through the sole, damaging vascular structures and crushing the living tissue of the sole and coronet, causing unrelenting pain and a characteristic lameness.

There are three phases of laminitis: developmental, acute, and chronic. The developmental (prodromal) phase often is completely undetectable. It occurs before any clinical signs of laminitis are noticeable. Experimental studies have shown it to last from 20 to 60 hours. In the last few decades, laminitis was thought to arise from disturbances of the blood supply to the laminar region, for example by vasoconstriction, microthrombosis, perivascular edema, or inappropriate arteriovenous shunting. The resulting lack of oxygen (hypoxia) was thought to cause degeneration of the dermal laminae. However, recent controlled studies have shown that if there is no vasodilation in the prodromal phase, no laminitis develops. They have also implicated certain enzymes (metalloproteinases) that are activated in an uncontrolled manner. These enzymes are normally present and are necessary to break down the basement membrane to allow normal growth of the foot. In laminitis, an unknown factor may trigger their activation, and they stay activated, leading to the loss of the basement membrane and ultimately to attachment failure. Presently there is no agreement whether there is vasoconstriction or vasodilation during the prodromal phase. Intense research is ongoing worldwide to find the answer.

The clinical signs of laminitis are similar regardless of the cause of the disease and can be divided into acute and chronic phases.

Acute Laminitis:

Acute laminitis occurs anywhere from 24 to 72 hours after the initial damage to the basement membrane and is heralded by the clinical signs of pain. Signs of acute laminitis include:

- severe lameness, reluctance to move, or even recumbency

- typical stance to try to get weight off the toes: front feet out in front if only the forelimbs are involved; all four legs in under the body if all limbs are involved; pointing with a leg if only one limb is involved

- increased digital pulses are almost always present (Fig. 4)

- heat in the foot; an unreliable measure because the temperature of the foot changes throughout the day; however, continued heat is often present with laminitis

- pain to pressure or percussion over the toe area

- systemic changes; anorexia, anxiety, increased respiration and pulse rates are often seen

|

(Fig. 4) The presence of arterio-venous anastomoses (AVAs) gives an alternate route for blood passing from the arteriole to the venule. When the AVA is open, blood can bypass the capillary bed and is unavailable to the tissues. Prolonged opening of AVAs in the digital circulation may be important in the early stages of laminitis. |

|---|---|

(Fig. 5)

|

Chronic Laminitis: Laminitis is considered chronic after 48 hours of lameness or after rotation and/or sinking of the coffin bone (Fig. 5). Rotation (the more common phenomenon) results from the laminae at the front of the foot separating; sinking of the coffin bone below the coronet band is from the letting go of the entire laminar junction. It is important that radiographs be taken to determine the actual position of the bone. Either or both of these changes to the position of the coffin bone may be mild or severe, even to penetration of the coffin bone through the sole of the foot.

The exact cause of laminitis is unknown. Occasionally, laminitis will develop for no apparent reason. However, usually laminitis develops as a sequel to a systemic disease or condition. Numerous predisposing factors have been identified. They can be divided into five major groups:

The treatment of horses that develop acute laminitis should be considered an emergency. It is imperative that the underlying primary disease is identified and treated as soon as possible by your Veterinarian. A delay of even a few hours can make the difference between a successful outcome and a failure. If any of the known risk factors for laminitis have occurred, therapy should be started before the clinical signs become visible. The treatment should be focused on elimination of the cause or triggering factor, blocking the pain, prevention of any further disruption of the attachment of the coffin bone to the hoof wall, promotion of healing, and maintenance of the systemic health of the horse. Until your Veterinarian arrives, the horse should be moved as little as possible and be encouraged to lie down by adding deep bedding to its stall if indoors. Don't feed anything to your horse nor administer any drugs unless advised to do so by the Veterinarian. Most of the recommended therapeutic regimens have value, but no one procedure has been shown to be superior to any other. If the laminitis progresses to the chronic stage, teamwork among you, your Veterinarian, and your farrier will become necessary for the best possible outcome for your horse. There will have to be a plan instituted involving dietary, medical, and therapeutic trimming and shoeing options. The time and cost may be prohibitive and a high level of dedication necessary and still the prognosis will be uncertain. In cases of acute laminitis, it will take at least eight weeks before any prognosis can be given; in chronic cases it can take from four months to a year before the future performance abilities can be estimated. Horses with more than 15 degrees of rotation accompanied by downward displacement of the coffin bone into the hoof capsule within four to six weeks of the initial episode of laminitis have a poor prognosis. Considering the enormous pain for the horse, it seems not humane to treat a horse with prolapse of the coffin bone through the sole. In protracted and/or severe cases of laminitis, euthanasia should be considered. |